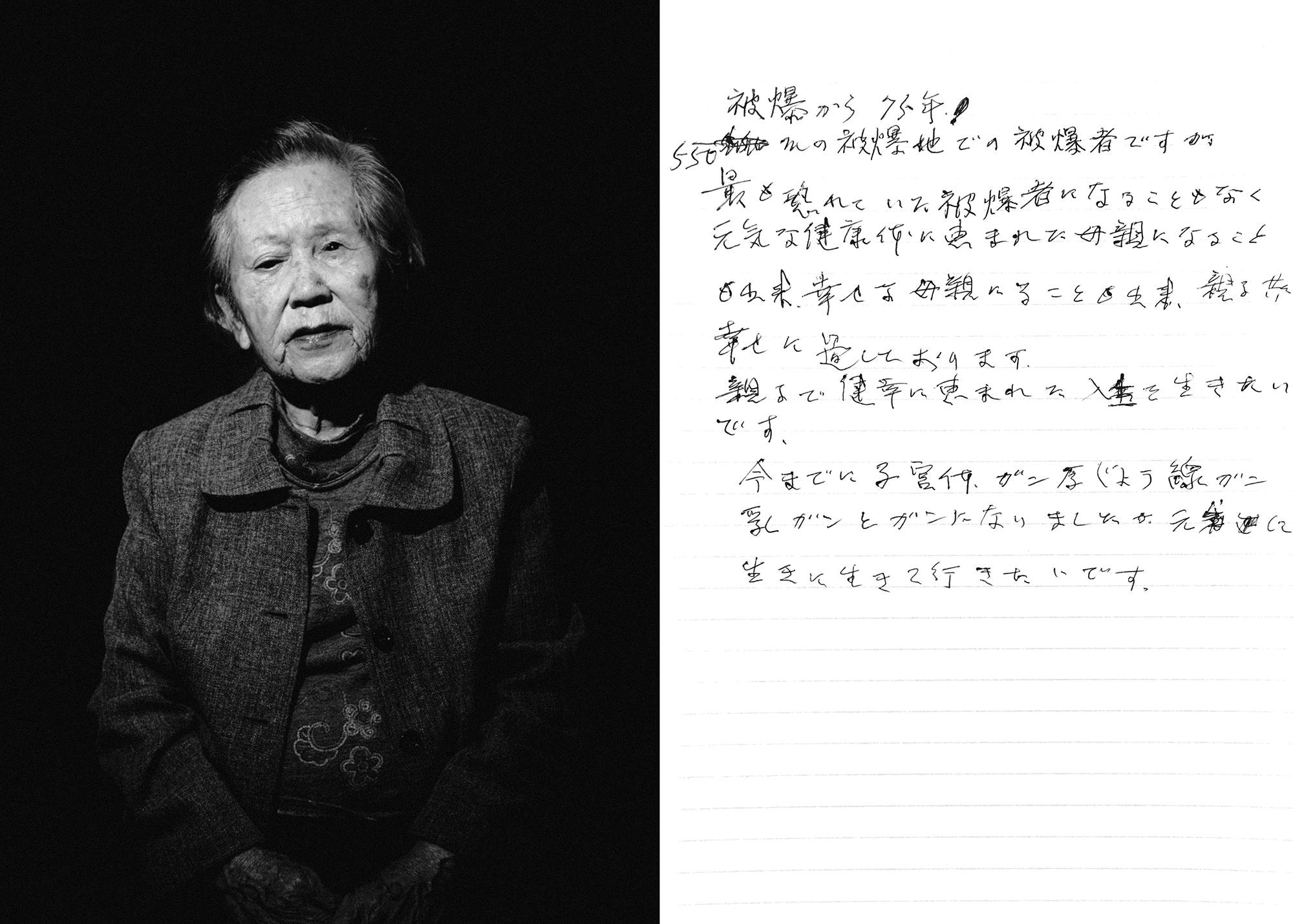

Ms. Taeko Teramae

Age: 88

Location: Hiroshima

Distance from hypocenter: 550m

“75 years since the bombing! Though I am a hibakusha who was exposed to the bomb 550m from the hypocenter, I did not become the hibakusha that I feared for the most. Instead, I became a mother blessed with healthy children, a mother blessed with a happy life, and I am currently living happily with my children.

I hope to continue living a life brimming with health and happiness, along with my children.

In the past, I have been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, thyroid cancer, and breast cancer. But I hope to live a healthy life.”

(Translated from an article Ms. Teramae penned for magazine publication Heiwa Bunka on July 1, 1985. Content has been edited for length and clarity.)

“I became a handicapped person due to the atomic bomb attacks. Glass shards pierced through my face, and left me blind in my right eye.

Back then, I was in my third year at Shintoku Girl’s High School and worked as a student laborer at the Hiroshima Central Telephone Exchange, 550m away from the hypocenter. Start times for the morning shift were staggered at 7am, 8am, and 9am. On August 6, 1945, my shift began at 7am.

That morning, I left my evacuation site at what is now Itsukaichi-cho on the first train out. I stood in line in the hallway to begin my shift when I glanced out the window and noticed a shiny object falling in the clear blue sky. ‘What is that?’ As soon as I turned to my friend, we were engulfed by a powerful flash that turned our surroundings bright white. Normally, I was not able to see past the buildings – but at this very moment, I was able to get a clear view of the entire city. Soon, a great cloud of dust wafted into my eyes and mouth, and everything went pitch dark. A loud boom! permeated the air, followed by the deep rumble of collapsing buildings. I began to choke on the consequent smoke – poisonous gas, it seemed like – and vomited uncontrollably.

‘Mom!’ ‘Mom, please help!’ ‘Mom, it hurts –’ When the dust settled, the hallway began to echo with young students begging for their mothers. Wakita-sensei, our homeroom teacher, yelled back, ‘Gakuto wa gakuto rashiku ganbarunoyo! (We must endure this, like the proud scholars that we are!)’ We were consoled by Sensei’s familiar voice, and the begging subsided.

I soon realized, however, that I could not move my body. A thick substance oozed down my face and into my mouth; my clothes were mysteriously drenched. (I soon learned that this was blood from the injuries on my face). I suspected that a bookcase in the hallway had fallen on me and pinned me to the ground. With much effort, I crawled out from under and searched for an exit, through pitch darkness. Since the stairwell was blocked with bodies piled on top of each other, I jumped out of the second-story window and climbed down a telephone pole. I made my way to Hijiyama for safety.

When I arrived at the cusp of the Kyobashi River, I turned back to see the city I left behind engulfed in a sea of fire. An immense fear took over me, and I could no longer look back. I had to escape, immediately. However, the river was at full tide and the only bridge, Tsurumibashi, was on fire. At this point my vision was faltering, and my face was painfully swollen. As I sat at the river bank in defeat, my shift manager from the telephone exchange, who had heard about my face injury, found me and handed me a batch of tobacco – a rarity back then – and applied it to my wounds. Soon, Wakita-sensei, who had also heard about my injury, came to my rescue.

‘The bridge is burning so we must swim across,’ she said. ‘Hang on to me tightly.’ I clung onto her arm as she pulled me through the current. I lost my vision completely about midway through the river. ‘We’re almost there!’ Wakita-sensei reassured me. ‘Hang in there!’

We finally made it to the other side, and Wakita-sensei took me to an evacuation center in Hijiyama. The facility was full of burn victims screaming in pain and begging for water. It was a true hellscape.

‘Wait right here,’ Wakita-sensei told me. ‘I have to go find Horikawa-san (another student with a serious injury).’ She then disappeared back into the city, the sea of fire.

That was the last time I saw Wakita-sensei. She saved my life, yet I was not able to tell her a simple ‘thank you.’ I deeply regret this, to this day. Wakita-sensei passed away on August 30, 1945, at the tender age of 20.

Thank you, Sensei.”