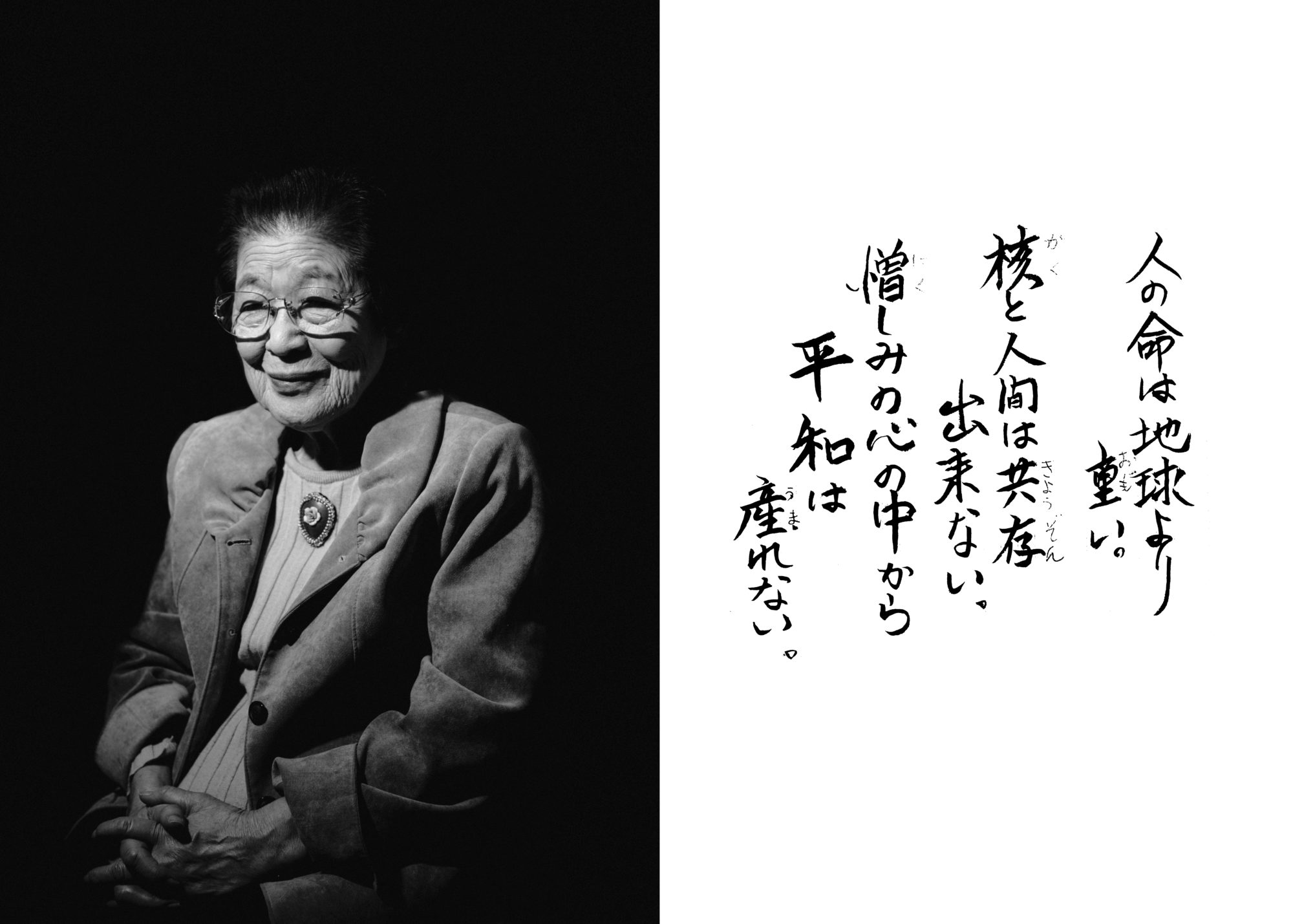

Ms. Megumi Shinoda

Age: 85

Location: Hiroshima

Distance from hypocenter: 2.8km

“A human life holds more weight than that of the earth. Nuclear weapons and humans cannot coexist. Peace cannot be born out of a hateful heart.”

“On the morning of August 6, I was expected to be at the demolition site as a student laborer. However, I fell ill due to long days working under the sun. My mother did not wake me up for work that morning. Perhaps she knew that I was exhausted, or was abiding by my father’s wishes.

My father spent 14 years in the US during the Taisho era as a laborer to send remittances back home. He knew a lot about the US. “We are destined the lose this war,” he often told us. “The US is an expansive country with plenty of natural resources. What do we have? Don’t force the children to go to school or the work sites,” he advised my mother.

When I woke up, it was too late to go to work. I leaned against a post in the sitting room and folded an origami crane for my two-year-old brother. My little brother stared intently at my fingertips, eating beans out of a bowl, one by one.

That was when our neighbor dropped by to borrow an ishigaki (stone grater). My mother emerged from the back, and the two began to chat. My little brother approached the neighbor with his bowl of beans. “Auntie, please have some –”

Suddenly, a great orange flame engulfed the side of our house, and set the shoji walls on fire. As I instinctively walked toward the kitchen for water, the tatami floors gave out from under me and I cowered over underneath the house as debris began to fall on my head. Moments later, it became eerily quiet. “Meguchan, meguchan,” I heard my mother call. As I emerged from under the floors, I saw that the entire house was in smithereens. My mother, brother, and the neighbor emerged from the cloud of smoke with severe burns on their bodies.

My mother and brother were in no condition to walk. I was the only mobile one. I walked to my aunt’s place 4, 5km away to borrow a rickshaw to carry my mother and brother to safety.

“What happened in Hiroshima?” my aunt asked me upon my arrival. “We felt the ground shake. The wind keeps blowing debris over here,” she told me. I notified her about my mother and brother’s condition. She offered me the rickshaw, and helped me carry it over the hill.

On the journey back, I encountered military officers treating burn victims in the bamboo forest. Trucks continued to pull up, dumping bodies by the load. I also encountered a group of burn victims walking toward me. Their hair was scorched off, revealing faces blackened with soot. Their tattered clothes hung limply over their bodies. I turned my head down as I passed them. I was the only one walking towards the city – with a rickshaw in tow, no less.

By the time I arrived home, it was dusk. One of my sisters had returned, and we got word that my other sister was also fine. However, we had yet to hear about my sister Sachiyo, who was working at a bank 500m from the hypocenter that morning. Later that evening, my father came home. He was relieved to see me, but when I mentioned that Sachiyo hadn’t returned, his eyes welled up with tears.

The next day, my father and I went to go look for Sachiyo at her workplace. As soon as we opened the doors to the bank headquarters, we were met with bodies crammed wall to wall, begging for water and calling for their loved ones. They all looked similar to the group I had encountered the previous day. It was truly a hellscape. “Is there a Sachiyo Sera here?” my father called out. We asked around, to no avail.

My father and I looked out toward the Aioi Bridge. There were corpses everywhere, scorched and blackened like the group from yesterday. There were children led by their mothers, mothers still clinging onto their children, individuals who could not bear the heat and had dunked their heads into the fire water tank. I remember seeing 2, 3 horses turned over with their legs splayed up, revealing swollen bellies split down the middle with yellow-ish entrails spilling out.

I also remember seeing a woman’s body laid upon a straw mat. “Who put the mat there?” I wondered. Beside her was a young boy – close to my brother’s age, about two years old – without a single scratch on his body. The boy was sitting there beside his mother’s corpse, alone. There were 5, 6 biscuits laid out in front of him. I still wonder, to this day, what happened to him. We couldn’t find Sachiyo that day.

We continued our search for Sachiyo the next day, to no avail. That evening, I woke up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night and saw my mother sitting alone, staring out into the street. “What are you doing?” I asked her. “Waiting for Sachiyo to come home,” she said, softly.

On August 15, the Jewel Voice Broadcast announced that Japan had lost the war. My father was right. As soon as the war was over, my cousin and older brother came home from the military. However, they both died of leukemia after going to my cousin’s dilapidated house 1.5km from the hypocenter to collect his belongings. They were so healthy when they returned from the military. I believe that they died from radiation sickness.

By September, my little brother’s burns were mostly healed. He had recovered well – in fact, whenever he heard an airplane overhead, he ran out into the front yard and yelled, “Give me back my sister! Give me back my sister!”

By October, however, he fell ill with chronic diarrhea – another symptom of radiation sickness. Due to the severe food shortage after the war, we couldn’t feed him anything substantial. “Mama, I don’t want to eat pumpkins anymore,” he said weakly as my mother wiped away her tears. Soon, my two and a half year old brother shrunk like a frail skeleton and joined my sister in heaven on October 22.”